KARACHI: On November 12, a United Nations official stationed in Afghanistan set the alarm bells ringing. While talking to CNBC, UN Development Programme (UNDP) official Al Dardani said that “Afghanistan is probably facing the worst humanitarian disaster we’ve ever seen.”

According to Al Dardani, around 23 million people in Afghanistan are in a desperate need of food and that the $20 billion economy could shrink by $4 billion or more with 97% of the 38 million population at risk of sinking into poverty.

“We have never seen an economic shock of that magnitude and we have never seen a humanitarian crisis of that magnitude,” he said, adding that funding for the humanitarian crisis and for essential services was crucial to maintain lives and livelihood in the country.

This crisis was set off by the suspension of funding by mostly Western donors in the wake of the Afghan Taliban’s lightning takeover of Kabul on August 16.

The US, which made a hasty and chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan at the end of its 20-year-long military campaign, also froze around $10 billion of the Afghan central bank held abroad – in a bid to stop the militants from accessing that money.

This suspension of funding and freezing of assets led to a collapse in public finances, and many workers stopped receiving salaries, which extended pressure on the Afghan banking system. According to the UNDP’s latest report issued on December 1, Afghanistan’s GDP could contract 20% within a year.

“The sudden dramatic withdrawal of international aid is an unprecedented fiscal shock,” UNDP Asia Director Kanni Wignaraja told AFP on Wednesday, as the agency released its Afghanistan Socio-Economic Outlook 2021-2022.

The report predicted that the economic contraction of around 20% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) within a year, could “reach 30% in following years.” For decades now Afghanistan’s economy has been undermined by war and drought. But it was propped up by billions in international aid.

“It took more than five years of war for the Syrian economy to experience a comparable contraction. This has happened in five months in Afghanistan,” Wignaraja said.

Another UN source told the AFP that, “in terms of population needs and weakness of institutions, it is a situation never seen before. Even… Yemen, Syria, Venezuela don’t come close.”

Previously, international aid represented 40% of Afghanistan’s GDP and financed 80% of its budget. But even reinstating aid now, while crucial, would be a “palliative” move, Wignaraja said. “[What Afghans need are] jobs, being able to learn, be able to earn and to be able to live with dignity and safety.”

The report also warned that depriving women of paid work in Afghanistan could fuel a GDP drop of up to five per cent, representing a loss of wealth of $600 million to $1 billion.

The Taliban have allowed only a portion of female civil servants – those working in education and health – to return to work, and have been vague on what the rules will be in the future. In the past, they banned women from working.

“Women constitute 20% of formal employment, and their jobs are vital to mitigate the economic catastrophe in Afghanistan,” Wignaraja told AFP. The damage “will be determined by the extent of enforcement or the delay,” the report noted.

In addition, there is a loss in consumption – women who no longer work no longer have a salary and can no longer buy as much as before to feed or equip their homes – which could reach $500 million per year, according to the UNDP. Afghanistan “cannot afford to forfeit this”, Wignaraja said.

Young Afghan women must also be able to continue post-secondary education, Wignaraja said. That means any education that “will help them … to contribute as they can and wish as doctors, nurses, teachers, engineers, civil servants or to run their businesses and build back the country.”

The worst victim of this economic crisis is, however, the children.

The UN’s children’s agency Unicef estimates that some 3.2 million Afghan children under the age of five will suffer from malnutrition this winter. A million of them could die in the absence of intervention. After 40 years of war, malnutrition is a perennial problem in Afghanistan, exacerbated in recent years by severe droughts. Since the Taliban takeover, unemployment has shot up, food prices have surged and suffering is visible across the country, particularly in camps for displaced people.

In view of the situation, the UN on Thursday appealed to the world community to donate a record $41 billion to provide life-saving assistance next year to 183 million people worldwide caught up in conflict and poverty, led by a tripling of its programme in Afghanistan.

In a report to donors, the world body said: “Without sustained and immediate action, 2022 could be catastrophic.” It said Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, Ethiopia and Sudan are the five major crises requiring the most funding, topped by $4.5 billion sought for Afghanistan where “needs are skyrocketing.”

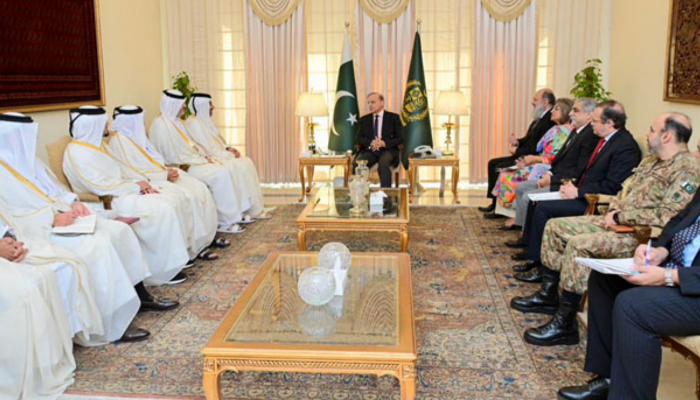

Meanwhile, Pakistan, in addition to giving an assistance of Rs5 billion and offering to host an extraordinary session of the OIC Council of Foreign Ministers, is taking urgent measures to cater to the healthcare needs of Afghans.

In addition to medical visa facilitation for patients at the crossing points and the provision of emergency life-saving medicines to Afghanistan, Pakistan has announced provision of medicines to the tune of Rs500 million at the earliest. [WITH INPUT FROM AGENCIES]