- Fans hate The Thing, Prince of Darkness by John Carpenter at first.

- Movies by John Carpenter, are now cherished classics in the canon of American horror cinema.

- These films were previously outright hated by critics and average viewers alike.

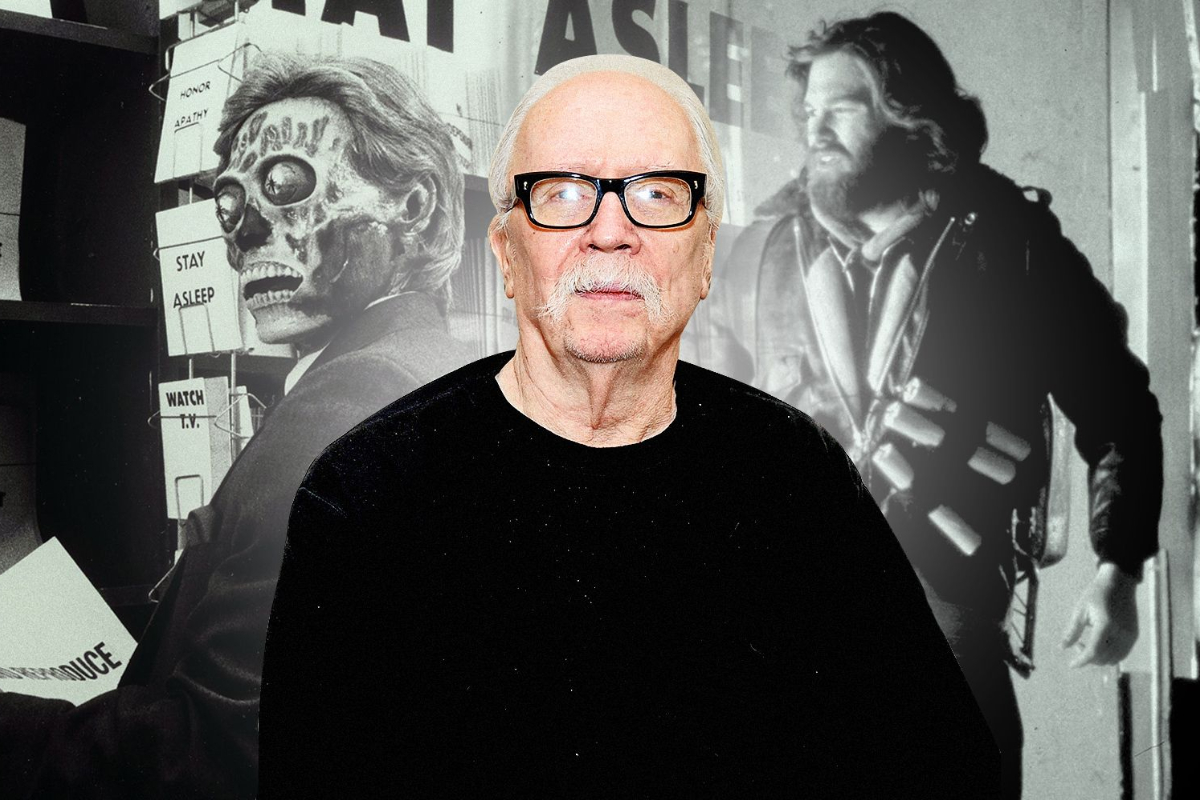

The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness, three self-described “Apocalypse Trilogy” movies by John Carpenter, are now cherished classics in the canon of American horror cinema.

In particular, The Thing evolved into a masterpiece that outperformed the status of the movie it was duplicating, to the extent that it is now used as inspiration for contemporary projects such as Halloween much to the delight of moviegoers worldwide, ends.

It can be perplexing to consider that these films were previously outright hated by critics and average viewers alike, given how well-regarded they are now.

That’s obviously no longer the case, as both researchers and horror fans support the image of Kurt Russell using a flamethrower to battle a shape-shifting extraterrestrial. Why, therefore, were these Carpenter films at first so hated?

When asked about The Thing’s critical reception, John Carpenter commented, “I was fairly startled by it.” I made a really dark, painful film because I believed audiences in 1982 would find it interesting.

No, they didn’t. The Thing was not well received by moviegoers of all demographics when it first opened in theatres, including critics. The Thing, according to Roger Ebert, is merely a bunch of spectacular special effects looking for a meaningful movie to occupy. Despite praising the film’s monster, Variety judged The Thing to be uninteresting overall.

The Thing received mainly negative reviews, yet its box office haul of $13.8 million on a $15 million budget was somehow far better. The Thing, a potentially large, VFX-heavy film that could compete with the summer blockbusters, was released at the end of June 1982, but it was overshadowed by other June 1982 releases like Poltergeist and E.T. : The Extra-Terrestrial.

Prince of Darkness, which was chosen to be released around Halloween, at least did better financially, earning $14.1 million worldwide. Critics, however, continued to be unconvinced by Darkness. Here, the main criticism was that there weren’t enough characters for the audience to care about, which was a problem that The Thing also suffered from.

When In the Mouth of Madness debuted in 1995, it was already obvious what kind of reception the movie would get from critics. Again, the Apocalypse Trilogy’s entry received mixed reviews. This time, the feature’s density was frequently criticized, with detractors objecting to its superfluous intricateness.

It’s quite acceptable to dislike any or all of the Apocalypse Trilogy films. Even if The Thing isn’t your cup of tea, you don’t have to hate on tough horror movies. That holds true for both contemporary audiences and critics of the 1980s and 1990s, who tended not to favor these films. There was no organized plot to deliberately target John Carpenter or these movies.

The bigger geopolitical context that may have influenced why general viewers didn’t flock to the movies in greater numbers is still worth exploring, though. In addition, all three movies have been interestingly misinterpreted by critics, who frequently vilify treasured elements of these flicks.

The reason The Thing and In the Mouth of Madness failed to become box office successes was because they were just out of step with popular culture. The Thing was a somber portrayal of people breaking down in the face of extreme adversity. It maintained this somber tone through an ambiguous ending that refused to provide audiences with clear-cut conclusions.

It’s understandable that audiences weren’t clamoring for this chilling horror film in 1982, a year when feel-good films like Porky’s, Annie, and Rocky III dominated the box office. Thirteen years later, In the Mouth of Madness attempted to scare viewers in a year when Species was the top horror film. Carpenter continued to produce classics, but the general public’s tastes simply weren’t in line with his darker, more introspective material.

Beyond just personal preference, there appears to be a discrepancy between what people expected from the Apocalypse Trilogy films and its creative objective, which may be the reason why viewers and critics failed to connect with them. It’s particularly intriguing how these movies are frequently criticized for lacking “relatable characters.”

Characters in The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness have amusing personalities, but the relationships between invented people aren’t always the focus of these films. The point of these three features—to varied degrees—is the ongoing mistrust between people.

The protagonist of In the Mouth of Madness, Jonh Trent (Sam Neill), is not defined by his friendly relationships with others, but rather by his terrifyingly rising realization that things are not as they appear. Kurt Russell’s R.J. MacReady, the protagonist of The Thing, is also not a people person and is instead defined by his varied reactions to the menace of a deadly alien hidden in plain sight.

The Apocalypse Trilogy films are primarily characterized by paranoia, mistrust of what appears to be everyday reality, and the possibility that the people you know aren’t quite who they seem. While the early criticism of these films frequently criticized them for deviating from standard character arcs or for using excessively violent death sequences, it neglected to acknowledge the artistic goals of these daring pictures.

[embedpost slug=”john-carpenter-reunites-with-halloween-station-wagon/”]