- Better Call Saul’s brilliant, emotional finale.

- Saul was finally caught and he negotiated a plea deal that would allow him to serve a maximum of seven years in prison before being released.

- He recognized an opening and seized it to clear the record of his ex-wife Kim Wexler and to restore his true identity

Better Call Saul’s brilliant, emotional finale. It turns out that there was one person that Jimmy McGill, both then and in the future, would put before his own self-interest.

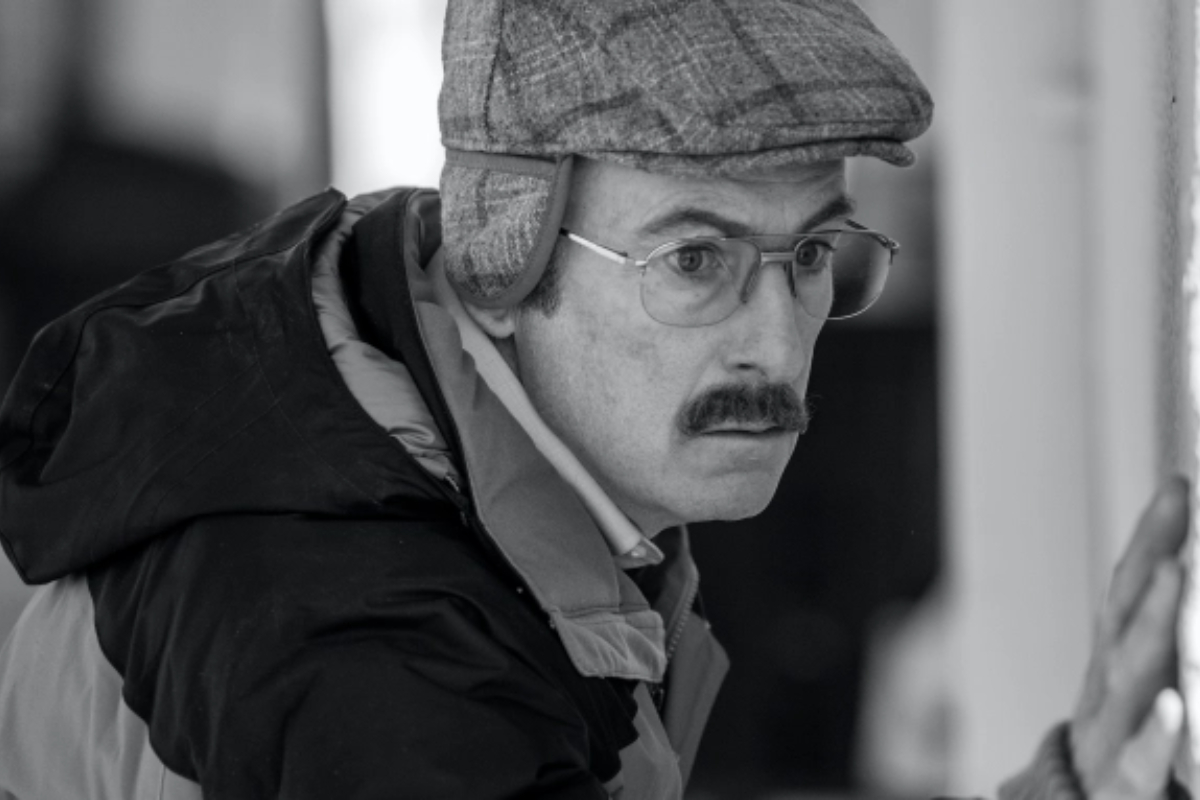

Bob Odenkirk’s portrayal of Saul Goodman, to use a term, “broke well” in the startling and sophisticated climax of one of TV’s most consistently excellent dramas from the previous ten years.

When Saul was finally caught, he negotiated a plea deal that would allow him to serve a maximum of seven years in prison before being released.

Then, however, he recognized an opening and seized it to clear the record of his ex-wife Kim Wexler (Rhea Seehorn) and to restore his true identity, which he had been using before “Saul” decided to devote himself entirely to deceit. Jimmy will most likely spend the rest of his life in prison, knowing that he was brought there in a merciful moment.

About fourteen years after the mothership of “Breaking Bad” first aired on AMC, this spinoff will likely come to an end. And with a small, fascinating tension, the “Saul” finale fits into the jigsaw created by Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould.

The setting for “Breaking Bad” was really gloomy. The deranged criminal Walter White got all he desired before dying, content in the knowledge that he was flawless, and it was probably too much for the lovers of that show. Now, the offshoot of that program denies us the juicy pleasure of witnessing Saul pull off one last major coup and forces us to consider the more nuanced satisfactions of going through pain for having made the right decision.

From the way it capitalized on Saul’s moral dilemma — with the mayhem of many peripheral characters participating in the drug trade becoming merely a list of crimes for which Saul must account — to the positioning of important supporting characters to buttress its arguments, this finale felt meticulous.

Odenkirk has perhaps never been stronger than in the courtroom scene, where he appears to be completely assured of his decision to use his legal expertise on another person’s behalf and yet is secretly delighted that the plan is succeeding.

Kim pretends to be her ex-attorney husband’s in order to enjoy a final cigarette in prison, a mournful reminder of all the con jobs they performed together in happier times. Seehorn’s acting as Kim continues to be electrifying.

While I’ve occasionally thought that “Better Call Sauldirect “‘s parallels to “Breaking Bad” were a little awkward, Bryan Cranston’s cameo as Walter in this episode’s flashback was well-deserved. The kingpin comments to his lawyer, “So you were always like this,” as they examine Saul’s early slip-and-fall con. According to what Walter tells himself, Saul was destined for crime; Walter was coerced into it.

When Saul starts getting abnormally philosophical and inquires as to whether Walter has any regrets, they talk. (If I had to make one observation about this scene, it would be that Cranston overplays Walter’s inability to comprehend the question; I’ve become acclimated to the less jarring rhythms of Odenkirk’s main performance and to “Better Call Saul” in general.)

Later, Michael McKean makes a second appearance in a flashback scene to depict Jimmy’s betrayed brother Chuck. The scene McKean and Odenkirk exchange is tender and mournful for what is to come; it is infused with Jimmy’s commitment to look after his brother, a promise we know he breaks. Jimmy observes Chuck reading “The Time Machine,” a book.

This conclusion functions somewhat like a time machine as well, and not just because it jumps around in Jimmy’s life. After much anticipation, “Breaking Bad” ended in a startlingly unsatisfactory way nearly nine years ago. The episode was well put together and read like a well-oiled narrative machine, but the simple conclusion lacked depth and substance.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that the show’s creator, Vince Gilligan, has frequently tried to weave in more of the plot. After the events of “Breaking Bad,” he followed Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul) in the feature-length movie “El Camino,” and he did the same with “Saul,” which provided him and Peter Gould (the episode’s writer and director) a second opportunity at a series finale.

For one viewer, “Saul” was an improvement above its prior series and a feat that would not have been possible without it. Its portrayal of “Slippin’ Jimmy” losing his composure struck saddening notes that the more operatic “Breaking Bad” couldn’t quite manage. This show has a greater sense of humor (and not for nothing).

The bittersweet parting of Jimmy and Kim—once united against the world and now divided by a prison wall, and the knowledge that one escaped their mutual pull towards the thrill of wrongdoing, but one couldn’t, quite—in the finale ratifies that sense once and for all, rivaling anything from “Breaking Bad.”

But as it communicated in glances rather than yells, it may not have been heard. The final thing we see of Jimmy is what Kim sees of him—a man who, if he weren’t so clearly a part of her past, would seem like a ghost to her. He is no longer visible due to a prison wall, and the camera follows her gaze as he leaves.

Overall, “Saul” will be regarded as a success from a period of television that appeared to finish before the program itself: It possessed a willingness to dally at the fringes of its plot and a faith in its viewers reminiscent of, say, “The Americans,” something that is far less common among today’s newer television shows.

(Notably, it ties back to the time when AMC was an emerging power behind adult dramas, a time that, barring a Sally Draper prequel series at some point in the future, appears to have come to an end.)

The choice made by the show to alternate important and stunning moments with prosaic sequences of characters’ everyday lives—a talk with a bartender, a day at the office—that seemed to go just a little bit too long was striking, especially in its final stretch of episodes. Although probably not what one would anticipate to be looking for in a show about a corrupt lawyer embroiled in cartel conflicts, it had the feel of real life.

But that’s what kept it going right up until the very end. It takes too long for the show to be repetitive and have Saul tell the story of his downfall to a judge in the last episode only so he can change it just enough to exonerate Kim. Once viewers understand what’s going on, the tease offers even more.

And it’s the final episode of a six-season confidence game that reverses what we saw on “Breaking Bad”: Those who were enthralled by Walter White’s transformation into Scarface got to see the never-ending antics of a man who, quite literally, could not stop doing wrong and who needed to pull out scams despite valiantly attempting to remain anonymous. Finally, he reveals what he had been hiding all along: a heart, human.

[embedpost slug=”better-call-saul-co-creator-found-it-hard-to-varnish-scene-after-bob-odenkirks-heart-attack/”]