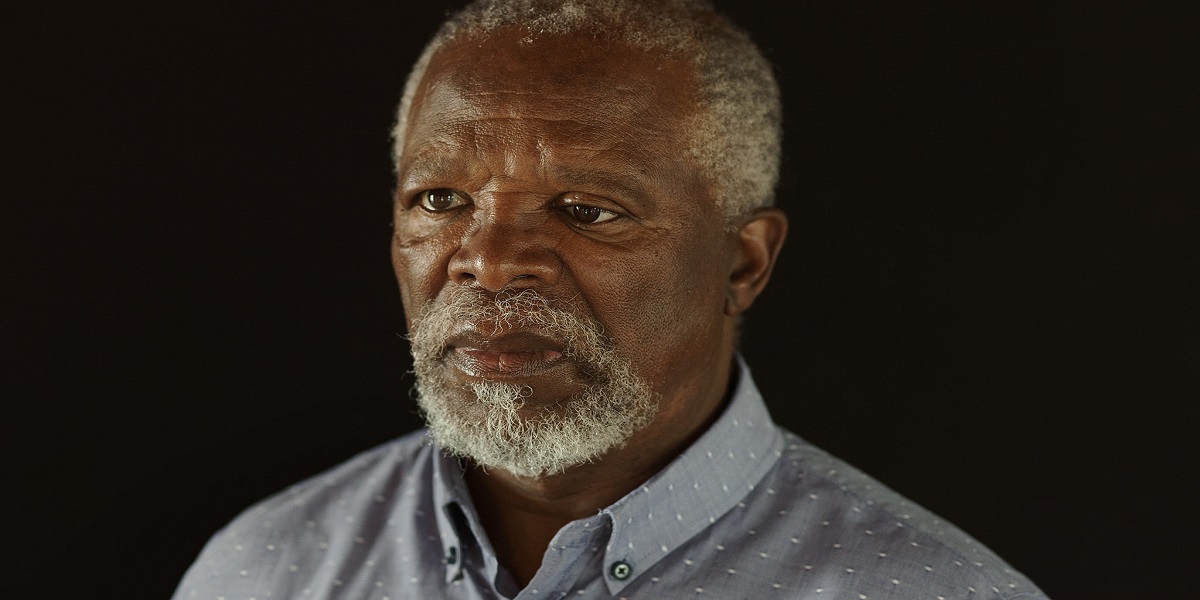

- When John Kani began his acting career in the 1960s, the only stage he could locate was an abandoned snake pit in a defunct South African museum.

- “Kunene and the King,” his most recent work, premiered with the Royal Shakespeare Company and ran in London’s West End.

- It is presently continuing a South African tour that was halted due to theatre closures caused by the epidemic.

“In 2018, I had the notion that we should commemorate 25 years of South African democracy since the start of the new, non-racial, non-sexist rainbow nation the following year,” Kani told AFP.

Lunga Kunene, an elderly black male nurse, is tasked in his play with caring for an older white actor dying of liver cancer but anxious to survive long enough to perform Shakespeare’s “King Lear.”

Read more: Shabnim Ismail and Luus saves South Africa from Ireland

“I wanted to make something that would compel the one who couldn’t live without the other,” Kani said.

He has unquestionably built a theatre about theatre, with Shakespeare coursing through its veins.

“I found myself quickly captivated in the history of these two individuals, from opposing ends of one nation, who perceive South Africa differently, but the only thing that would bring them together is their love of Shakespeare,” he explained. “And that’s how King Lear became intertwined with the plot.”

The two characters recite words from Shakespeare’s play, emphasising Lear’s struggle with death.

They also recite lines from “Julius Caesar,” both from the original play and from a translation into Kani’s home tongue, Xhosa, that he remembers reciting in high school in 1959.

Kani is now touring with South African actor Michael Richard, who says the narrative uses King Lear’s metamorphosis to reflect how South Africa is developing.

“In the play, Lear learns about mankind. And in this play, my character learns empathy as a means of reconciling with South Africa “explained Richard

– Theatre about theatre –

Kani’s traumas unexpectedly began to manifest in real life.

In the British presentations, he was joined by South African-born actor Anthony Sher, a knighted Shakespearean performer. Sher died of liver cancer in December, the same ailment that kills his character in Kani’s play.

His younger brother died of liver cancer in 2019, just as the play was coming together.

Despite the tragedy, the play is also incredibly hilarious, which may come as a surprise to younger fans who may remember Kani best for his roles as the Black Panther’s father in the Marvel flicks or as the shaman mandrill Rafiki in the 2019 “Lion King” adaptation.

Kani is a renowned character in South African protest theatre. His snake pit pieces in the 1960s brought him into contact with Athol Fugard, widely considered as one of the country’s best playwrights.

They resisted apartheid-era segregation regulations by gathering in secret and holding rehearsals in classrooms and garages, despite frequent police scrutiny.

They took the moniker Serpent Players and played classics such as “Antigone” in a snake pit at an unloved museum.

Read more: South Africa: 15 dead, 37 injured in bus collision

“It was a museum with an amusement park,” Kani explained. “On the other side, you’d see the dolphins, and when Port Elizabeth was very bad economically, everyone would plead, would someone please let the dolphins out before you shut up the place?”

Kani, Fugard, and fellow artist Winston Ntshona were composing new plays by the early 1970s that showed the brutal reality of living under apartheid.

Kani and Ntshona received a Tony Award in 1975 for their performance of “Sizwe Banzi is Dead” in New York.

All three also wrote “The Island,” a key drama depicting the circumstances of imprisonment on Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela and other leading campaigners were imprisoned.

Today, South African theatre is suffering, with audiences still limited to 50% capacity under Covid laws.

Kani believes the play is being viewed differently now that the virus has caused so much disease and death throughout the world.

People “understand the process” of disease and death now that the play is post-Covid, he says. “Africans have a deep respect for both death and life. They recognise the process and the trip, but they regard it as a continuance of life.”