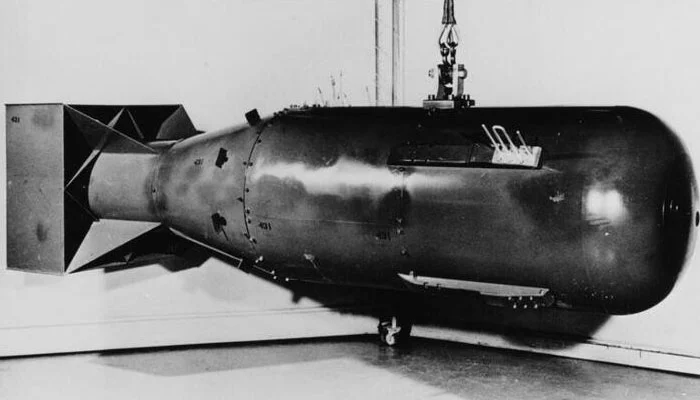

How many nuclear weapons are there, and who owns them?

Castle Romeo was the code name for one of the tests in the Operation Castle series of American thermonuclear tests conducted at Bikini Atoll beginning in March 1954. Photographer: Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

The threat of nuclear weapons use has increased since Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine nearly three weeks ago.

This was made clear on Feb. 27 when Russian President Vladimir Putin declared his country’s nuclear forces to be on “high alert,” according to the Associated Press. According to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the current situation is a “nightmare scenario” come true.

So, what did Putin mean when he said his country’s nuclear weapons were on high alert? In addition, how many nuclear weapons are there?

According to the Arms Control Association, the world’s nine nuclear states—China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—possess approximately 13,000 nuclear warheads in total. This estimate, however, is based solely on publicly available data; there could be many more that states have not disclosed.

“We know which countries have nuclear weapons, but we don’t necessarily know how many nuclear weapons they have; Israel, for instance, does not publicly acknowledge its program,” Anne Harrington, a senior lecturer in international relations at Cardiff University in the U.K., told Live Science. “The number of nuclear weapons China has is also a major subject of debate.”

HOW MANY NUCLEAR WEAPONS ARE OUT THERE?

Both the United States and Russia have reduced their respective nuclear arsenals since the Cold War’s end, and their nuclear stockpiles are far smaller than they were at their peak. According to Homeland Security Newswire, the United States had 31,225 nuclear weapons in 1967. According to a Harvard Kennedy School report written by Graham Allison, a national security analyst at the school, at the time of the Soviet Union’s demise in 1991, approximately “35,000 nuclear weapons remained at thousands of sites across a vast Eurasian landmass that stretched across eleven time zones.”

According to a January fact sheet released by the Arms Control Association, Russia currently has 6,257 nuclear warheads, while the US admits to having 5,550. This drastic reduction, however, is “primarily due to them dismantling retired warheads,” Sara Medi Jones, a campaigner for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), told Live Science.

According to Jones, “there was actually an increase in deployed warheads last year [2021], and all nine nuclear-armed states are either upgrading or increasing their arsenals.”

“Although it’s difficult to know definitively exactly how nuclear arsenals are changing, we assess that China, India, North Korea, Pakistan and the United Kingdom, as well as possibly Russia, are all increasing the number of nuclear weapons in their military stockpiles,” said Matt Korda, a senior research associate and project manager for the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists.

HOW QUICKLY CAN NUCLEAR WEAPONS BE DEPLOYED?

There is “a bit of a spectrum” in terms of how quickly a nuclear weapon could be deployed and how many are on “high alert,” according to Korda. The United States and Russia keep a portion of their nuclear weapons on high alert, which means they could be ready to launch “in less than 15 minutes,” he said. According to a 2015 paper by the Union of Concerned Scientists, the United States and Russia each had around 900 weapons on such high alert.

Other countries, such as China, Israel, India, and Pakistan, keep their nuclear weapons in centralised storage, which means they would have to be removed and “mated to their delivery systems in a crisis,” according to Korda. This could take days, if not weeks, to organise.

Others, like the United Kingdom, have nuclear weapons “deployed at all times on ballistic missile submarines,” but these are kept in detargeted mode and would take “hours or days to bring to launch-ready status,” according to Korda.

HOW POWERFUL ARE THE NUCLEAR WEAPONS OUT THERE?

The destructive power of nuclear weapons varies. The most powerful bomb in the United States’ current nuclear arsenal is the B83, which has a maximum yield of 1.2 megatons and is 60 times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, in 1945. The Nuclear Weapon Archive reports that 650 B83s are in “active service.”

The B83’s destructive capability, however, pales in comparison to the most powerful bomb ever made: the Soviet Union’s “Tsar Bomba,” which had a yield of 50 megatons—approximately 2,500 times more powerful than the weapon that destroyed Nagasaki. The Tsar Bomba was a one-of-a-kind weapon designed to demonstrate the Soviet Union’s military might, and no further iterations of the weapon have been produced to date.

Nuclear fusion is used in hydrogen bombs such as the B83 and Tsar Bomba, whereas fission is used in atomic bombs. There is no comparison in terms of destructive power: hydrogen bombs have the “potential to be 1,000 times more powerful than an atomic bomb,” according to a Time magazine article reprinted with permission by the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum.

Another important distinction is whether a nuclear weapon is classified as “strategic” or “nonstrategic,” according to Korda.

Strategic nuclear weapons can “reach from Moscow to Washington, D.C.,” according to Samuel Hickey, a research analyst at the non-profit Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation.

“On the surface, it appears logical to assume that ‘nonstrategic’ weapons have lower yields and’strategic’ weapons have higher yields,” Korda explained via email. That is usually the case, but it is not always the case.

Even “low-yield” weapons have the potential to be extremely lethal. The Trump administration proposed and developed the new “low-yield” W76-2 submarine-based warhead, which has a yield of approximately 5 kilotons. In comparison, the “Fat Man” bomb dropped on Nagasaki by the US had a blast yield of 21 kilotons and was estimated to have instantly killed around 40,000 people. Many thousands more died as a result of long-term health effects caused by the bomb, such as leukaemia.

“There is no way to use one [nuclear weapon] without escalating a crisis and murdering civilians,” Hickey told Live Science. “Just this past January, the leaders of China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States together affirmed that ‘a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,’ as the consequences of a single weapon detonation would be catastrophic.”

HOW ARE NUCLEAR WEAPONS STORED?

While each country has its own system, storage facilities are generally blast-resistant and are often buried underground to “limit the damage of an accidental detonation and to protect against an attack,” according to Hickey.

Nuclear weapons in the United States are “kept under cryptographic combination lock to prevent unauthorised use,” according to Hickey. Only the president has the authority to authorise their use in theory, but Hickey claims that “if the cryptographic code is input or bypassed, the nuclear weapons could be armed in a matter of minutes.” Hickey did, however, confirm that these weapons would need to be “affixed to a missile or deployed on an aircraft” before they could be launched.

Given that the launch of a nuclear weapon would, in all likelihood, be met with immediate retaliation and could lead to all-out global nuclear war, is there a chance that all nuclear weapons could be decommissioned for the greater good? Could there ever be a future without nuclear weapons?

I don’t think this is going to happen,” said Holger Nehring, chair in contemporary European history at the University of Stirling in Scotland. “Nuclear weapons are mainly a form of deterrence against nuclear attack, so states have no real interest in getting rid of them. Entirely getting rid of nuclear weapons would mean a very high level of trust between all states in the international system, and this is unlikely to be achieved.”

Andrew Futter, a professor of international politics at the University of Leicester in England, agreed. “We have probably reached a point now where further big reductions are unlikely,” he told Live Science.