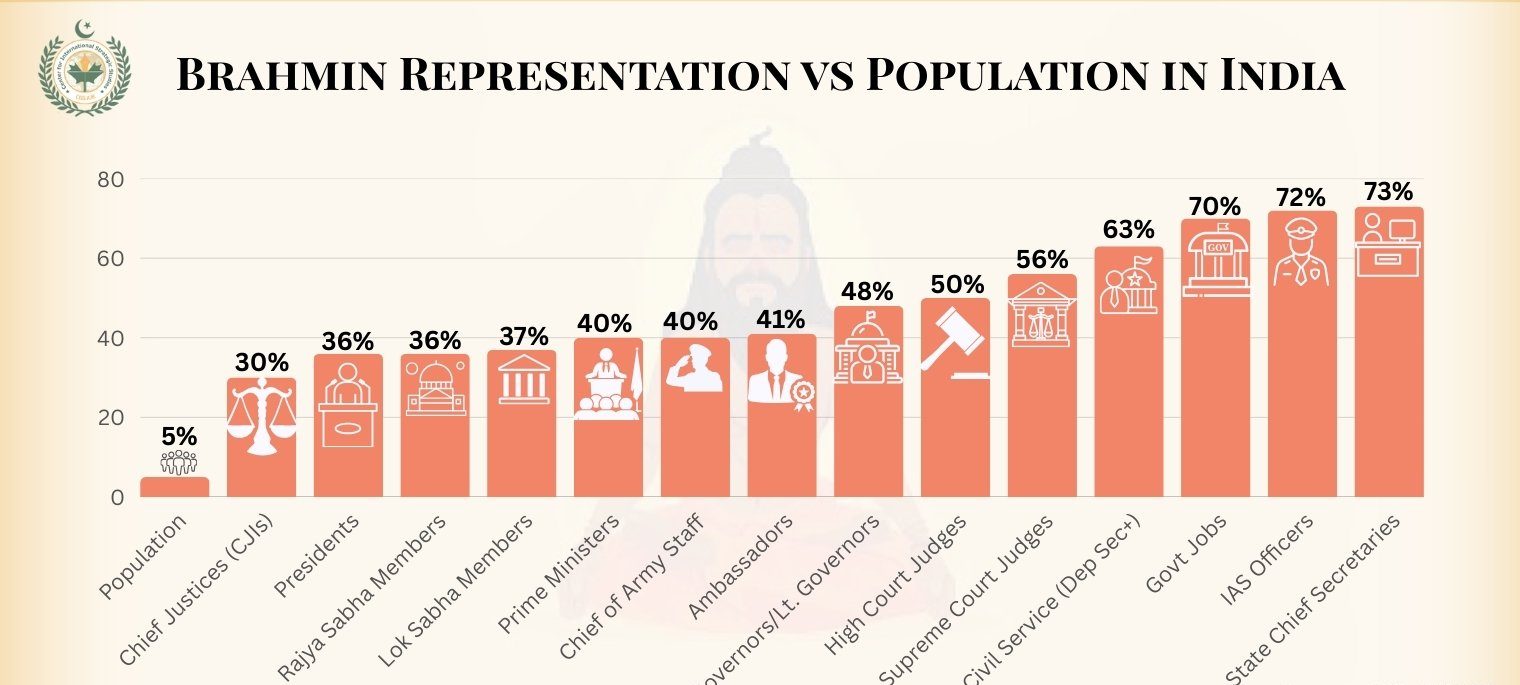

In a nation as diverse and complex as India, questions of representation and equity remain central to its democratic ethos.

Despite comprising just 3–5% of the country’s population, Brahmins—traditionally regarded as the priestly and scholarly caste—continue to occupy a disproportionately high number of positions in India’s most powerful institutions, from the judiciary and bureaucracy to academia and media.

The infographic, widely circulated across social media platforms and academic forums, underscores a striking contrast: while Brahmins are a numerical minority, they continue to hold a majority of top positions in the judiciary, civil services, academia, foreign service, and politics. This includes a significant number of prime ministers, presidents, and key bureaucratic roles held by individuals from this community since India’s independence.

Scholars and social critics refer to this phenomenon as “Brahminocracy”—a deeply entrenched system wherein the principles of democratic equality are undermined by structural caste privilege. According to critics, this concentration of power has led to a silent, persistent form of exclusion that affects the majority of Indians, particularly Dalits and other marginalized communities.

“Most people think caste is just about untouchability or rural discrimination,” said Dr. Anjali R., a sociologist specializing in caste and inequality. “But caste, especially as enforced through Brahmanism, dictates who gets access to education, land, jobs, cultural capital, and even self-worth.”

Caste System Legacy Lives On:

The hierarchical Varna system, which assigns Brahmins to the top position and Dalits to the bottom, dates back roughly 3,000 years. While legally abolished, its legacy continues to shape Indian society in the form of social stratification, economic disparity, and institutional bias.

Dalits, who have historically been subjected to untouchability and systemic oppression, still face barriers in accessing education, property, and dignified employment. Meanwhile, caste privilege ensures that the upper castes, especially Brahmins, continue to enjoy better opportunities and societal esteem.

In urban and rural India alike, caste continues to influence everything from marriage to employment and political representation. While affirmative action policies exist to address these inequities, critics argue that dominant caste groups still wield outsize influence over how power and resources are distributed.

Calls for Structural Reform:

The data has prompted calls from academics, activists, and citizens for deeper structural reforms—going beyond reservation quotas to address caste-based overrepresentation and underrepresentation at the systemic level.

“This is not just about counting heads,” said Dalit rights activist Praveen Kumar. “It’s about understanding how caste privilege is reproduced in schools, universities, courts, and parliaments. If Brahmins are just 4% of the population, why do they still control most of the institutions that run the country?”

The conversation around caste, privilege, and representation continues to evolve, with growing awareness among younger Indians. However, experts warn that without a fundamental restructuring of access to land, capital, education, and cultural power, caste hierarchies will remain embedded in India’s democratic framework.

This imbalance has sparked renewed debate over caste privilege, meritocracy, and the structural inequalities that shape access to power in modern India.